Image

By clicking Submit you verify that you are 21 years of age or older and agree to our cookie policy.

Submit

In 2015, Freemark Abbey went through renovations to Antonio Forni’s historic 1898 stone building. The goal was to create a more hospitable venue for its visitors. Changes were extensive, but it was a reminder to Freemark visitors and employees alike that this storied property has been evolving for many decades.

A slightly earlier improvement occurred around 1990: a fountain was constructed in the courtyard, under which, according to longtime employee Sue Cottrell, a Freemark Abbey time capsule is buried—but more on that below.

In his second volume of A History of Wine in America, wine historian Thomas Pinney includes a photograph of an unadorned, stone winery facing Highway 29. There’s a large basket press visible to one side and in the foreground, in block letters, a “Visitors Welcome” sign installed over a patch of scrub. The photo offers no clues as to which winery this was or is, though the caption identifies it as Freemark Abbey in St. Helena. Pinney notes that it was taken “in the 1950s, when Napa tourism was simple and direct.”

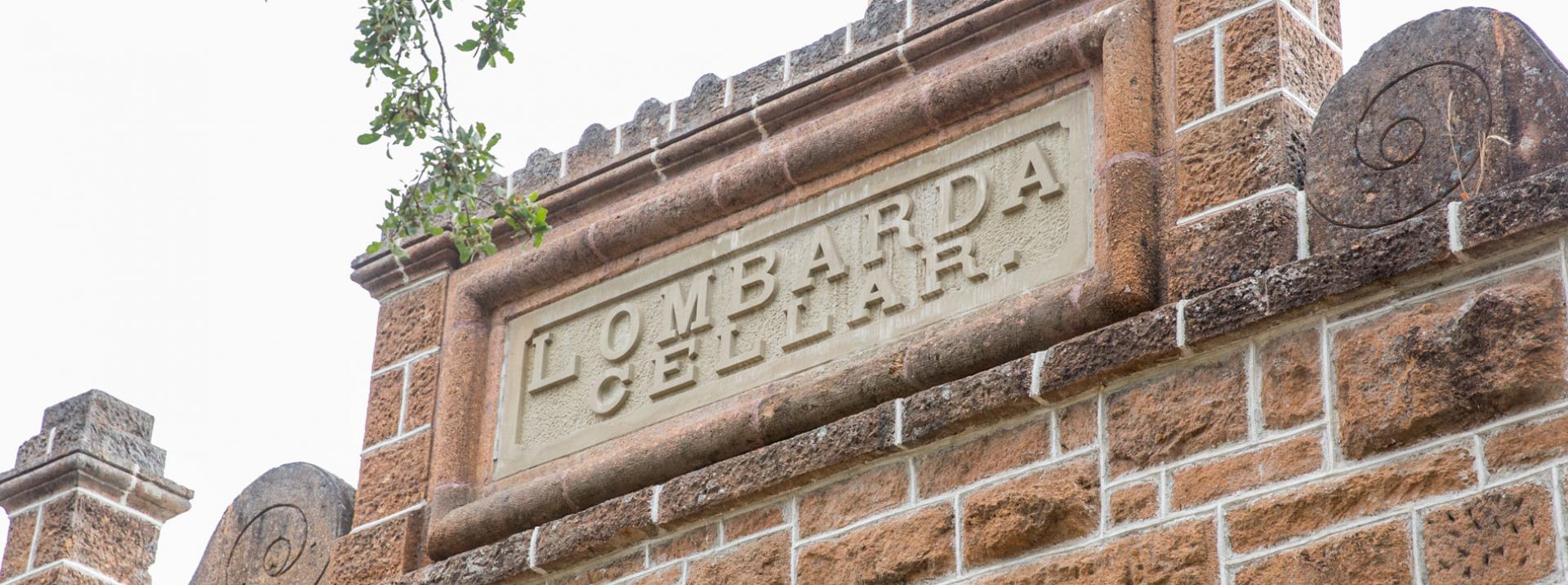

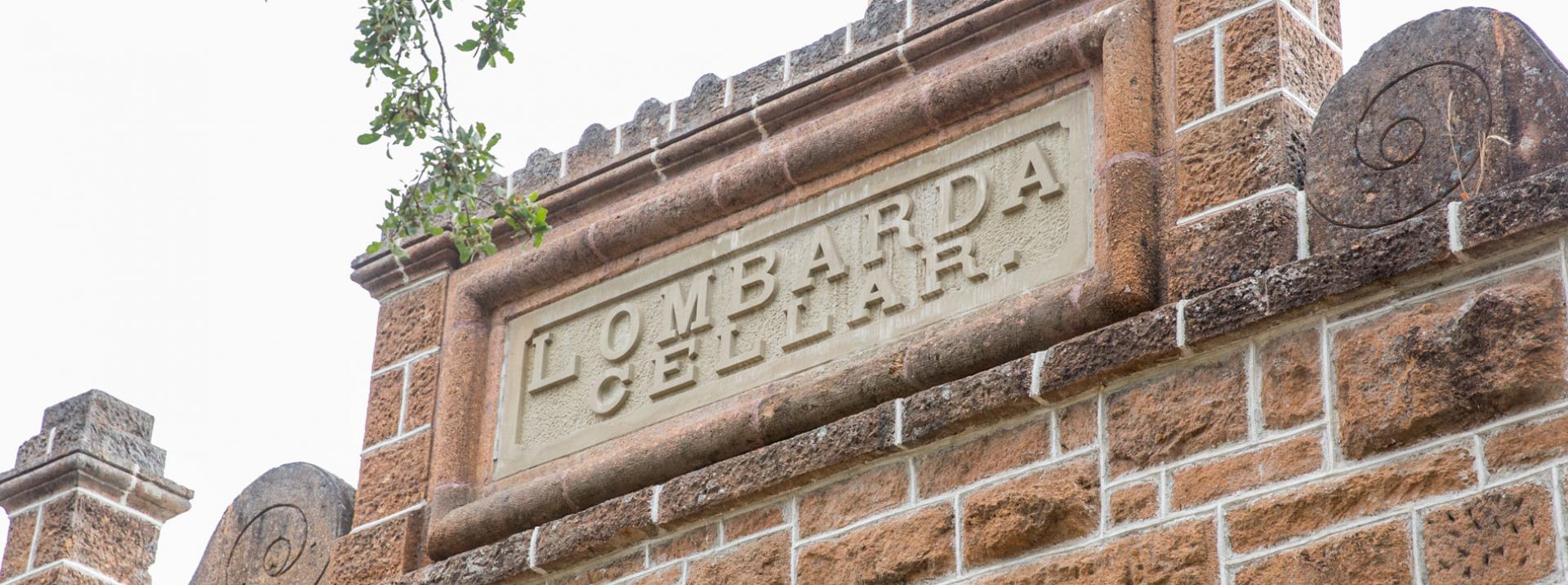

Back in 1940, Albert “Abbey” Ahern and his business partners, Charles Freeman and Mark Foster, purchased the Forni family’s Lombarda Winery property and combined their names to form the Freemark Abbey moniker. Then in 1949, the trio opened a “sampling room.” They were among the earliest Napa Valley proprietors to create space for what would become commonly known as a “tasting room,” where visitors were offered sips of the wines made right there on the property. 70 years later, that tasting component of a winery visit is more or less expected, but back then it was a rather novel idea.

So, in addition to giving their names to Freemark Abbey, the three partners helped bestow on Napa Valley an identity that endures and thrives to this day: a place for hospitality.

It’s hard to believe—or overstate—how far the Valley has come as a wine tourist destination since the “simpler” days of the 1940s, 50s, and 60s, when traffic on Highway 29 was light, and there were fewer than fifty wineries between Napa and Calistoga.

“This first Freemark Abbey Winery operated for twenty years,” Pinney’s fellow wine historian, Charles Sullivan, writes in Napa Wine, A History. The partners closed it after Ahern’s death in 1959, but, as Sullivan notes, “during that time the winery produced a wide variety of wines.” He explains that, while a handful of others like Ahern arrived in Napa Valley in the 1940s, “the trickle would grow in the fifties and sixties and become a flood in the seventies.”

It was that decade of the 1960s that saw the rebirth of the Freemark property.

“The lights at Freemark Abbey came back on in 1967,” the historian later notes in Napa Wine, “when a partnership headed by Charles Carpy bought the old Lombarda place.” Carpy and his six partners soon ramped up both the winery’s production and reputation.

Sullivan points out that “Cabernet Sauvignon made the Freemark Abbey reputation, specifically the wines made from John Bosché’s twenty acres in Rutherford,” the property that would become the source of Freemark’s signature wine, Cabernet Bosché.

Then in 1976, the Judgment of Paris tasting introduced Napa Valley wines to an international audience. Of the dozen California wineries chosen to compete, Freemark was the only one that included both a red and a white wine.

In her own way, Sue Cottrell is a direct connection to that 1970s heyday.

She arrived in St. Helena in 1970 with her then-husband to open Cuvaison Winery just north of town. “My former husband had a doctorate in laser optics, which, of course is a wonderful background to make wine,” she joked on the phone recently.

“The person from whom we learned the most and who gave us the most expertise was Bill Bonetti, who was the then-winemaker at Charles Krug. Without his time and expertise, I don't think we would've ever made any wine there.”

The couple eventually sold Cuvaison, and Sue started working at Freemark Abbey in 1982.

Though retired, she rivals Ted Edwards for the length of her Freemark tenure. Ted is still going strong after 35 years at the winemaking helm; Sue spent 31 years in a variety of hospitality-related positions at the winery. Anyone wondering what the contemporary history of Freemark Abbey looks like should consult her.

“Harvest was the most exciting season,” she shared in a separate email, reflecting on her early days at the winery. “Guests would watch grapes being dumped into the hopper and pressed. Employees working at either the press or the tanks inside the winery often answered questions posed by curious guests.”

She noted “the tour always began with a brief history of Napa Valley and the founding of Freemark Abbey by Josephine Tychson. Often we pointed to the nearby hillside home of Josephine! And I made a point of explaining where Freemark Abbey fit into the historic presence of the first wineries in Napa Valley, and especially the importance of both Bosché and Sycamore Vineyards, each privately owned by the Bosché and Bryan families, with whom Freemark continues to have long term contracts.”

She recalled that she and her Freemark colleagues hosted events at both Sycamore and Bosché Vineyards, especially around the Napa Valley Vintners’ June Wine Auction. “We also hosted events at Carpy Ranch and Red Barn Ranch, which is now Frog’s Leap Winery. It was the site of many a harvest party.”

On the phone, she clarified about that time capsule.

Looking at an old photo of the property reminded her that she’d once heard about the engraved “Lombarda Winery” sign coming down in the 1940s to be replaced with a Freemark Abbey sign. Behind the stone sign, a stash of money and an old newspaper were supposedly discovered—or maybe this was just hearsay.

Either way, she said, “it gave me the idea in the early 90s, when they put it in the fountain, of making a time capsule. And so I got a strong box and put a bottle of Bosché in it, along with a work order, our Christmas picture that year, a corkscrew or an Ah-so opener—I can’t remember which—and some comments about the grapes from Ted. It's documented in some file at Freemark Abbey. There's a photo of someone putting everything in the strong box, what the box includes, and then the box was actually placed under the fountain as the concrete was poured over it.”

No one would accuse Sue of not having fun in her job.

To this day, she has great memories of Chuck Carpy and his partners, who were regular presences at the winery in the 1980s and interacted closely with the Freemark staff. She was particularly fond of the partner and original winemaker, Brad Webb.

“Brad was the one who was probably the quietest but also had the most influence on the wine,” she said. “Ted was there when Brad was still alive and appreciated his influence.”

Echoing Sue’s recollection, Charles Sullivan writes that Webb “set the tone for the style of Freemark Abbey wines in the years to come.”

Sue continued, “You know, day-to-day at the winery it would be Chuck and Laurie Wood. And each month our staff would get together for lunch, and we'd usually have a speaker. Oftentimes it was somebody within the winery, and the best one was Laurie Wood, who would recount his days in the second landing at Omaha Beach or helping to build transcontinental Al-Can Highway. I mean, he had incredible stories. We kept saying, ‘And what happened then, and what happened then?’

“Laurie and Chuck were present every day. We would see Brad periodically, and then we would of course see John Bryan, who owned Sycamore Vineyard. We didn't see Dick Heggie as much, although whenever we had an event, which were frequent, all the partners would come with their spouses. The Heggies in particular, who were world travelers, had a real comfort level. They always chose to sit with the cellar crew and communicate with them in Spanish, which was great.”

Then Sue paused and laughed, “I’ve only scraped the surface here. The stories abound! Where to begin?”

She acknowledged that the three decades she spent at Freemark Abbey were just a chapter in one of Napa Valley’s great winery histories. When—or if—that time capsule gets opened, more tales will no doubt spill out of it.